News

TrueTimber and Banded Partner with Darby’s Warrior Support

October 28, 2025 •iSportsman Staff

DST Ends November 2, 2025. The iSportsman system may experience technical difficulties at this time. View system updates here.

August 28, 2025

As you hit the beach for your final hot-weather hurrah, here’s something to think about: This summer marks 50 years since Jaws slammed into theaters, rattling sand buckets and planting a seed of fear in millions every time they stepped a toe into the ocean. Directed by Steven Spielberg (it was the famous directors first, big commercial success) and based on Peter Benchley’s novel, Jaws wasn’t just a summer hit—it invented the summer blockbuster. It delivered wide release, massive TV advertising and a simple, high‑concept premise told with suspense and minimalist shark reveals. Until Star Wars came along two years later, it was the biggest-grossing movie ever.

From a fisherman’s standpoint, Jaws was a master class in perception management. There, the shark, particularly the great white, is cast as the villain—relentless, malevolent and lurking always just beneath the surface. That emotional gut‑punch changed the way Americans looked at the waves. Beach attendance dipped in 1975 as a result, and Jaws spawned imitation thrillers, shark‑fishing tournaments and a visceral fear known as the “Jaws effect”—a learned trepidation toward sharks.

Benchley eventually went on to denounce his own creation’s unintended fallout; Spielberg later confessed regret too, both noting how Jaws contributed to an overkill of the shark population—an irony few of us expected when snapping lines from sun‑soaked docks or the deck of a boat. The website, Mental Floss, notes that widespread overfishing has driven shark populations down roughly 70 percent since Jaws hit screens—though climate change and commercial pressures are at play too, there’s no denying the movie didn’t help.

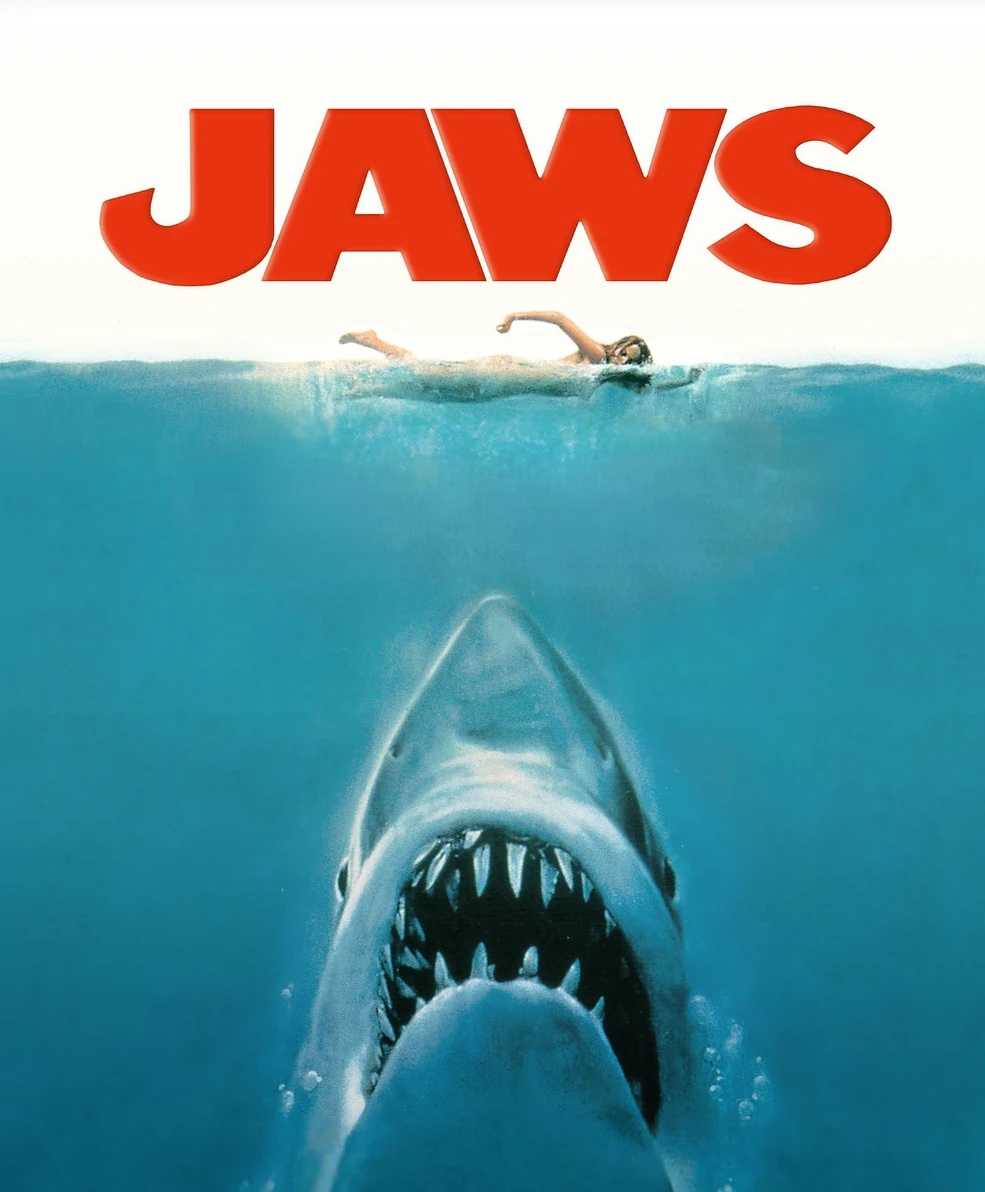

The Jaws original movie poster.

But let’s get to what really matters: real‑world numbers. How often do sharks actually bite? According to the Florida Museum’s International Shark Attack File, the world averages about 64 unprovoked shark bites per year—and only around 9 percent of those are fatal, roughly six deaths annually. That’s right—six deaths, globally, per year (which is six too many if you are one of the unlucky ones to be fatally attacked).

Still, if you want perspective in 2024, the U.S. tallied 28 of the world’s 47 unprovoked shark bites (Who provokes a shark bite? Apparently, 24 people did!)—nearly 60 percent of all cases. Florida alone accounted for 14 of these, or about half the U.S. total. Since the 1800s, some 1,660 U.S. unprovoked shark attacks have been recorded—Florida leading the pack with 942 strikes since 1882.

Let’s zoom in on the great white, the red‑tinted star of Jaws. As of 2024, there have been 351 recorded unprovoked great‑white bites, with 59 of those resulting in death. That’s more than five decades, leaving us with less than 10 fatal bites per year globally from great whites.

As more people have flocked to beaches for summer vacations and like to live along the coast, unprovoked shark bites overall have increased in sheer numbers since 1950—from about 50 per year mid‑century to over 80 in 2020, with a spike to 111 in 2015. But relative to human population size, the rate per million people has stayed flat—or even dropped slightly.

In the real world, sharks aren’t the ocean’s featured predator of humans. At sea, they don’t target us. Most bites are cases of mistaken identity. If you’re nervous about sharks, it helps to know this: shark attacks remain extraordinarily rare. You’re more likely to get struck by lightning than bitten by a shark. That said, various prevention measures—drum lines, nets, shark‑spotting and electronic deterrents—are deployed in hotspots to reduce already tiny risks, mostly to make people feel better than anything else.

And as for the individual, to reduce your odds of being attacked by a shark when swimming, the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission recommends swimming in groups, staying close to shore, not going in the water bleeding, avoiding shiny jewelry when swimming and even avoiding bright colored clothing or uneven tan lines as sharks can be attracted to contrasting colors.

Of course, there’s the obvious one, too, that famed Thunder Ranch founder, Clint Smith, believes everyone should follow. Smith, one of our nation’s most legendary firearms instructors and a certifiable Marine (Ret.) badass, who earned badassery status fighting in the jungles of Vietnam, admits to one fear: sharks. So, you can always do what he strongly recommends: Just stay the hell out of the water.